By Karen Yancey

The Washington Island Observer this year is celebrating its 40th year of providing news and information to its readers that is “all about the Island.”

For more than a century, newspapers have provided a way to get information to their readers that is defined as news – timely, close to home, unusual, involving notable people or events and/or impacting the reader. At their best, newspapers provide objective information on issues that is not slanted by the opinions of the writer or newspaper owners. As important, newspapers encourage a dialogue on issues faced by a community.

At the local level, the current board and staff of the Washington Island Observer seeks to provide objective, accurate and high-quality reporting on news and issues that affect the Island. And through the Observer’s Letters to the Editor page, anyone can write to express their views on these issues.

Island at a crossroads

This year, with the pandemic receding, Washington Island residents and property owners are at a crossroads. More people than ever before are visiting the Island – whether as day tourists or as vacationers who come for a week or longer stay on the Island. At the same time, the Island has seen an influx of young families, both families who have moved here from other parts of the country and those who are descendants of some of the Island’s first settlers. They will be the Island’s leaders by 2040 and it is important that we help them realize their vision of a thriving community two decades from now.

As many people have commented this summer, “Washington Island has been discovered.” Vacationers who used to come to the Door County peninsula due to its scenery, recreational opportunities, quaint shops and towns, and peaceful environment are now choosing to escape the crowds on the peninsula by spending some or all of their vacation time on Washington Island. This is putting a strain on our municipal budget and services from garbage collection to beaches but is also helping many local businesses to succeed. We need to find a way to balance these interests.

Global trends like the rapid increase in the world’s population and the impacts of climate change are also affecting the Island. There are simply more people who need a place to vacation. In addition, the heat waves, droughts, and wildfires on the East and West Coasts are causing more people to see the Midwest and the abundance of fresh water on the Great Lakes as an attractive place to vacation and live. In parts of the Midwest, wealthy people from both the East and West Coasts are buying land and homes off the Internet in case they need to escape the threats of climate change. Do we want the Island to become a place of empty homes waiting for climate refugees and how worried should we be about this trend?

All these issues could change the Island in the years ahead. If the Island community simply reacts to them, residents may not like what the Island has become by 2040. Many of those qualities that brought full-time and seasonal residents here – that make the Island a special place – may be lost. Whether current full-time and seasonal residents came here for the beauty of the Island, its maritime history, strong community, business opportunities, love of the arts and music, ecological health and open spaces, family ties or its tranquility, they may find many of these qualities displaced in the years ahead if the Island community does not develop a plan to preserve them now.

Planning for the future

This a plan should be based on a vision for the Island that most residents share – what they hope will be retained and what will be changed on the Island by the year 2040. To encourage people to think and talk about these issues, the Observer board has invited speakers with expertise in a variety of areas to tell us how we can shape the Island’s future and what we can expect in the years ahead if we don’t take an active role in this future.

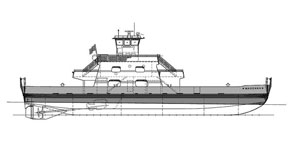

We have named this exchange of ideas “Island Forum 2040.” This year, we have scheduled three speakers on the future of Island schools, business environment and ecological health. In addition to the Observer, the other sponsors of “Island Forum 2040” are the Trueblood Performing Arts Center and the Washington Island Ferry Line. The TPAC stage for these events will not only include the speaker but also three or four Islanders who are leaders in this field to ask questions of the speaker when he or she is finished with their half-hour presentation. Questions from the audience will also be welcomed. All the presentations begin at 7 p.m. and cost $5.

In 2022, we will have an additional five to seven speakers on everything from the future arts and music culture of the Island, to managing tourism to the future of our churches. We will also ask experts involved with the health of Lake Michigan and from other Great Lakes islands to speak. Hans Lux, town chairman, has agreed to attend all the presentations and notices are being sent to all the town board members as well.

In fall of 2022, we will ask all our panelists, as well as other interested Islanders, to attend a special meeting with an experienced leader in helping not-for-profits, municipalities and corporations develop vision statements and strategic plans. We hope this group can develop a vision statement for the Island in 2040 as well as help us chart a course to make this vision happen.

Our first 2021 speaker is State Representative Joel Kitchens (R-Sturgeon Bay) on Aug. 16, who will direct his remarks to future state funding for rural schools, as well as other state issues that may impact the Island in the years ahead. The panelists will be Michelle Kanipes, Island school principal, Sue Cornell, Island school superintendent of business services, and one or two members of the Island school board.

In addition, Steve Jenkins, executive director of the Door County Economic Development Corp., will speak about developing sustainable Island businesses for the future on Wed., Sept. 8; and the Island’s Jesse Koyen, who is now director of stewardship for the Door County Land Trust, will discuss protecting the ecological health of the Island’s land and lakes on Sept. 23.

So please mark your calendar for these dates and plan to attend. As Margaret Wheatley, the celebrated writer and community builder, notes, “There is no power for change greater than a community discovering what it cares about.”

The Washington Island Observer would like to thank the 35 families who invested in the Observer almost a decade ago and allowed the current board and staff to offer this platform to begin a dialogue on shaping a vision for the Island’s future. Tickets can be purchased at the Observer office prior to the event or at the TPAC office on the night of the event.